Grandpa Warren Reese Peters Sr

"From Darkness to Light"

Baseball bat thrown, its cruel path unseen,

Across young eyes that sparkled in the sun,

Till blackened nights replaced where light had stun,

And shadows grew where childhood had been seen.

Across young eyes that sparkled in the sun,

Till blackened nights replaced where light had stun,

And shadows grew where childhood had been seen.

Yet through the dark, a strength within him grew,

A keen, sharp sense to guide him through each day,

With touch and sound, his world isn't even gray.

And love, like the dawn, still made it's way through.

He sought a cure, a flame within his chest,

That burned for the sight of his mother's smile.

A plea to heal, to end his darkness' trial.

Light returned but with colors never blessed.

And with restored sight, he lived unrestrained,

His world reborn, no longer shadow-chained.

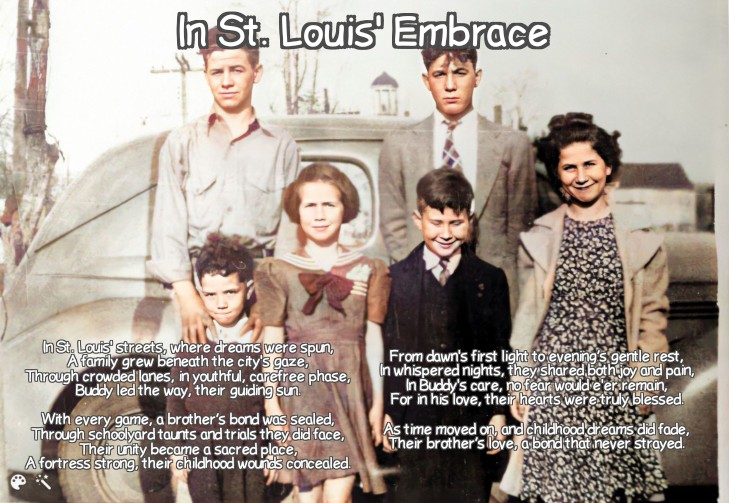

"In St. Louis' Embrace"

In St. Louis' streets, where dreams were spun,

A family grew beneath the city's gaze,

Through crowded lanes, in youthful, carefree phase,

Buddy led the way, their guiding sun.

A family grew beneath the city's gaze,

Through crowded lanes, in youthful, carefree phase,

Buddy led the way, their guiding sun.

With every game, a brother’s bond was sealed,

Through schoolyard taunts and trials they did face,

Their unity became a sacred place,

A fortress strong, their childhood wounds concealed.

From dawn's first light to evening’s gentle rest,

In whispered nights, they shared both joy and pain,

In Buddy's care, no fear would e'er remain,

For in his love, their hearts were truly blessed.

As time moved on, and childhood dreams did fade,

Their brother’s love, a bond that never strayed.

Both poems have been created from these anecdotes that was shared by his sister Aunt Alene Peters Sitton:

Warren Reese, affectionately known as “Butter” by his younger brother Aaron, had a unique childhood. When Warren was in the 4th or 5th grade, a schoolyard bully hurled his baseball bat at him, striking him across the eyes. The impact left Warren with black eyes and swollen features.

As time passed, Warren’s sight gradually faded until he could only distinguish between daylight and darkness. He attended a school for the blind, where he spent seven or eight years. During one visit home, he surprised his sister Alene by recognizing her touch and voice while feeling his nephew Don’s crib. Alene attempted to startle him, but Warren’s keen senses revealed her presence.

Later, the family moved to Arkansas, and Warren decided to escape the confines of the blind school. He hitchhiked from Jacksonville, Illinois, all the way to East St. Louis, where he sought refuge in their father’s apartment. Concerned for Warren’s well-being, their father insisted he return to Arkansas.

Eventually, Warren agreed to attend the Little Rock Arkansas Blind School. There, he faced a pivotal decision: an experimental drug that could potentially dissolve the clot on his optical nerve. Warren implored his father to sign the consent form, emphasizing that he couldn’t bear a life of blindness. His plea worked—the drug succeeded, and Warren regained his sight. He was about sixteen or seventeen years old at the time.

Warren’s resilience and determination transformed his life, proving that sometimes even the darkest moments can lead to unexpected light.

Buddy frequently visited our house and eventually went on to high school. He was more than just a friend; he was my confidant, my laughter partner, and sometimes even my sparring companion. We were true pals. As time went by, Buddy ventured out, working various jobs here and there.

Before our family faced the challenges of being burned out, Warren and his Adventist friend Johnny observed the Sabbath by taking Saturdays off. And, of course, Sunday became another day of rest. It’s amusing to note that one of the Adventist groups had a rural background. Buddy, still rooted in his small-town upbringing, hadn’t encountered much wildlife beyond his experiences at the blind school.

Our rented farm, nestled between Gentry and Siloam Springs, housed a couple of cows, a horse, and several calves and pigs. One memorable night, Warren returned home with an unusual tale. He had attempted to catch a cat in one of the barns—a civet cat that emitted a skunk-like odor. The encounter left Warren’s clothes so foul that they had to be burned. He scrubbed himself clean in an outdoor tub, and we tried various remedies to rid him of the stench. Unfortunately, the barn didn’t escape unscathed either.

In August 1946, Lorraine, Don, and I found ourselves home alone. Our pressure gas stove was being refilled by Lorraine when the gasoline can suddenly ignited. Reacting swiftly, I grabbed the can and rushed it outside, but not without spilling some gasoline on myself as I threw it out the door. The flames had already engulfed the wall, and soon the entire house and its contents were consumed.

Lorraine lifted me out of the flames, and together with Don, we were taken to the hospital by a visiting preacher who happened to be nearby. My body bore the scars of the fire—forty-five percent of it burned. I was in dire condition, and at fifteen years old, I longed for my brother, Buddy.

After about two weeks, Buddy finally returned to Arkansas and made his way to the hospital. It was the middle of the night, and I strained to hear his voice asking, “Where is she? Where’s my sister?” Despite the nurse’s attempts to delay him until morning, I couldn’t contain myself and screamed, “Buddy, Buddy!” The nurse realized he was my brother and ushered him in.

Buddy stayed by my side, ensuring I ate and cared for me. He’d take a bite, then feed me. When the doctor visited, he expressed relief that Buddy had arrived. “Thank God you got here, Buddy,” he said. Shortly after my release from the hospital in October, Buddy headed to San Bernardino, California, and later migrated to Salt Lake City.

Buddy’s unwavering presence during those difficult days remains etched in my memory—a testament to the bond between siblings that transcends even the darkest moments.

Comments

Post a Comment